From the Margins to the Spotlight: Restoring the Legacies of Gilded Age Black Men of Distinction

August 11, 2025

The Real History Behind The Gilded Age’s Black Characters: African American Journalists and Physicians Who Defied Racism

Throughout American history, the stories of African American achievement have been diminished, denied, or outright ignored by the mainstream historical record. When African Americans of distinction did make it into press, their coverage was often couched in racist and condescending language, designed to belittle rather than celebrate their accomplishments.

The main stream press distorted many African American achievements. The press rarely honored their accomplishments. Through TV representation their stories are being rescued and revived. There is little published or known about the affluent Black life at the end of the 19th Century. HBO’s The Gilded Age has been instrumental in exploring the nuanced realities of the lives of affluent African Americans in the late 19th century.

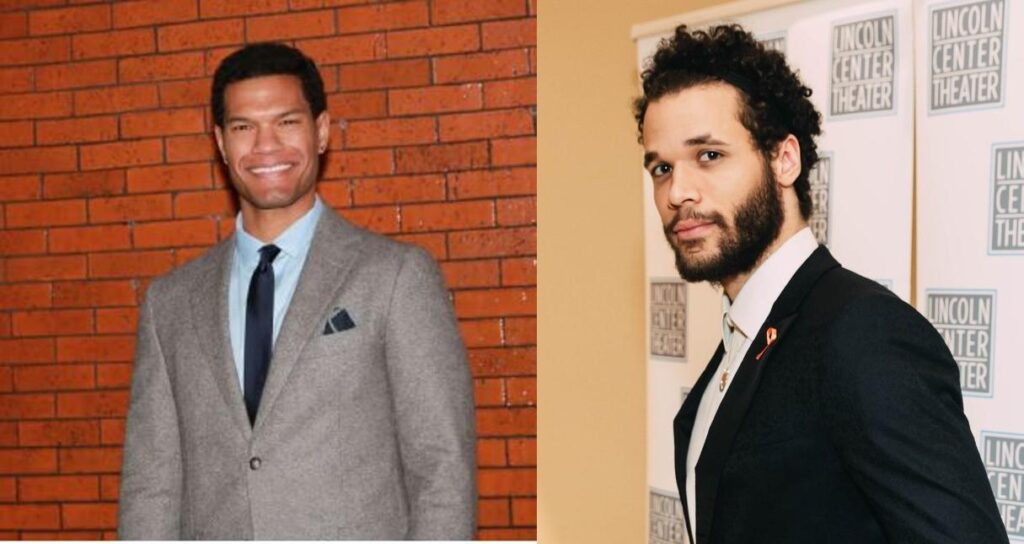

Two characters T. Thomas Fortune played by Sullivan Jones and Dr. William Kirkland played by Jordan Donica —offer a rare counterpoint to this tradition of erasure. Fortune is a real historical figure, one of the most respected African American journalists of his time. Kirkland is fictional, but his character draws upon the lives of several pioneering Black physicians, whose biographies remain largely unknown to the wider public. While there were a number African American physicians practicing in the U.S. from 1860-1890 many were froced find training in Canada and Europe.

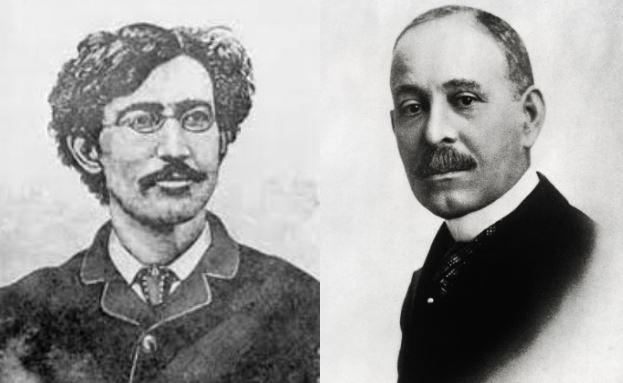

T. Thomas Fortune (1856–1928), born into slavery in Florida, became the “Dean of Negro Journalists” and a leading voice against lynching, disenfranchisement, and segregation. Through his newspaper, the New York Age, Fortune championed civil rights, economic empowerment, and the dignity of African Americans during an era when white supremacy sought to crush both. In The Gilded Age, his depiction rings true, capturing both his intellectual vigor and his unshakable principles.

Dr. William Kirkland, though a fictional character, is rooted in historical precedent. His portrayal borrows elements from Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who performed one of the first successful open-heart surgeries and founded the nation’s first non-segregated hospital, and Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta, the first African American faculty member at a U.S. medical school—Howard University’s College of Medicine in 1868—and the first African American to be appointed as a surgeon with the rank of Major in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Augusta went on to head Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., and became a key figure in training future generations of Black physicians. In the latter part of the 19th century, numerous African American physicians practiced in the United States, but many had been forced to obtain their medical training in Canada or Europe due to racial barriers at home.

This was also the era in which eugenics—a pseudoscientific, racially biased theory that sought to justify white supremacy—was gaining intellectual traction among America’s political, academic, and medical elite. Eugenicists argued that African Americans were biologically inferior, using flawed data and biased studies to rationalize segregation and limit access to professional advancement. In medicine, these beliefs had devastating effects:

- Hospital Privileges Denied: Black physicians were systematically excluded from admitting privileges at white hospitals, forcing them to work in underfunded Black-only institutions with fewer resources and lower pay.

- Professional Isolation: Organizations such as the American Medical Association barred Black doctors from membership, isolating them from the latest research and professional networks.

- Medical School Discrimination: Eugenics advocates lobbied to limit the number of Black students admitted to medical schools, claiming they were unfit for the profession.

- Public Distrust: White supremacist propaganda fueled mistrust of Black doctors among white patients, effectively closing off a large segment of potential clientele.

Despite these barriers, Black physicians persevered—founding their own hospitals, medical societies, and training programs, often at great personal and financial sacrifice. Their resilience laid the groundwork for later generations of African American medical professionals and civil rights activists.

In the late 19th century, when the mainstream press covered men like Fortune or Williams at all, it was often through a lens of exoticism, condescension, or suspicion. The accomplishments of Black physicians were particularly underreported, buried in medical journals or Black-owned newspapers with limited reach. Period dramas like The Gilded Age and The Knick begin to fill this gap, offering audiences glimpses into the lives of these men. But selective storytelling is not enough—these narratives should be told with full historical fidelity to the Black experience.

Bringing these biographies back into the American consciousness is more than an act of historical recovery—it’s a reclamation of truth. These men were not outliers or footnotes; they were leaders in the ongoing struggle for equality, role models for their communities, and innovators in their professions. Whether through fictionalized television dramas, documentary films, or biographical features, their stories deserve to be told in a way that honors both their achievements and the barriers they overcame.

The erasure of Black excellence was intentional. Restoring it must be deliberate. By rescuing these lives from the edge of oblivion, we tell a fuller, more honest American story—and remind ourselves that the Gilded Age was not gilded for everyone, but it was also not without its Black luminaries, fighting to shape the future. #GildedAge, #AmericanHistory, #BlackHistory, #HistoricalFiction, #CivilRightsHistory

A review of The Master

September 23, 2012

Freddie Quell is a drunken sailor with a combat related stress disorder and a drinking problem played by Joaquin Phoenix. He returns from World War II after a stint in the South Pacific unable to hold down a steady job drifting on a course of self destruction. He washes up on a boat sailing from San Francisco to New York under the direction of Lancaster Dodd founder of the Cause a sci-fi cult doctrine espousing time travel back to former lives to cure current ills. The character Lancaster Dodd was inspired by and loosely modeled after Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard. While The Master is supposedly Quells story Dodd’s equally compelling biography competes for top billing.

Dodd seems to believe he and Freddie Quell share a past and manages to endear himself to the misfit. While Quell is initially skeptical of the charismatic Dodd’s teachings he remains open and submits to a “Processing” a first step analyses. The Cause “process” is eerily similar the Scientology Dianetics, L Ron Hubbard’s belief that individuals can free themselves of mental disorders and phobias by facing the traumatic incidents or “engrams” that block one’s mind. Quell grows into a believer indeed a Dodd protector and bodyguard until the son Val Dodd (played by Jesse Plemons) exposes his father as a fraud. Dodd sets out to cure Quell of his alcoholism or perhaps more to brain wash in an attempt to gain complete submission to the Cause.

Freddie Quells passes time as a member of the cult family but his manner and actions come into frequent conflict with others. Quell’s loyalty to Dodd seems conflicted despite his violent defense of the crackpot. Wracked by the memories of a youthful romance Quell finally realizes Dodd is con-man and stages his escape from Dodd’s hold. He participates in a motorcycle game driving off into the Arizona sunset failing to return. Years later Dodd tracks Quell down from his newly established London school and beckons Quell to join him. Upon arrival Dodd as The Master demands Quell’s complete submission to the Cause. The film climaxes with two men competing free wills clashing before departing.

It’s a complex surreal tale with Quell’s sexual libido frequently surfacing. The cinematography, costumes and sets are superbly and amazingly authentic and true to the 1950s era.

The Master was written, directed, and co-produced by Paul Thomas Anderson. He has written and directed six feature films: Hard Eight (1996), Boogie Nights (1997), Magnolia (1999), Punch-Drunk Love (2002), and There Will Be Blood (2007). He has been nominated for five Academy Awards, There Will Be Blood for Best Achievement in Directing, Best Motion Picture of the Year, and Best Adapted Screenplay; Magnolia for Best Original Screenplay; and Boogie Nights for Best Original Screenplay. Anderson has been hailed as being “one of the most exciting talents to come along in years” and “among the supreme talents of today.” The Master had its premiere at the 69th Venice International Film Festival. Anderson compared Phoenix’s commitment to that of Daniel Day-Lewis for his level of concentration stating that Phoenix got into character and stayed there for three months.

This is the first film of 2012 receiving Oscar buzz due a large part to the Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman. Both may contend for Oscars as best actor and best supporting actor.

Chocolate City’s gentrification and the trail of tears

August 5, 2012

Gentrification is destroying whole communities leaving lower income residents homeless and hopeless seemed to be Saturday’s message from the special screening of Chocolate City sponsored by Maximize Good at the Watha T. Daniel Public Library. A discussion with filmmaker Ellie Walton and DC residents followed. While the film was shot in 2003 almost a decade later the message is resonating with greater urgency. The documentary covers the displacement of over 400 families who lost their battle against forced displacement from the Arthur Capper/Carrollsburg public housing project in Washington, DC. Filmmaker Ellie Walton views Chocolate City as a call to action against nationwide gentrification and redevelopment programs. The film explores the impact of rapid gentrification in the area through the work of a local group of women working for justice in their neighborhood.

In 2001, DC received a $34.9 million Hope VI grant to redevelop the 23-acre Capper/Carrollsburg public housing project as a mixed-income community, with the 700 public housing units to be replaced one-for-one, along with 1,000-plus market-rate and workforce-rate rental and ownership units and 50 Section 8 ownership units. The project is scheduled to be completed this year.

The 400 displaced families were promised a one-to-one replacement of all demolished public housing units. That is, for every one family displaced they would be replaced with a unit in the new housing project. However residents later discovered lower income residents did not qualify. Income qualifications based on regional median income standard disqualified a majority of renters with few qualifying to buy. The average median household income inside the beltway is $90.

Hope VI requires mixed income residents meet an income threshold of 60% of the regional average median income. Many of the former residents were minimum wage earners and financially barred from returning. The reality is that mixed income does not include low income. The former residents soon found additional barriers to reentry including a vague rule that only residents in “good standing” would be allowed to return those without past felony convictions.

As the discussion progressed many spoke with concern about the unfairness of current policies with some telling of their own displacement. In the film examples were sited on how the loss of community and its support resulted in the death of older displaced residents. In the discussion a participant identified as Daniel born and raised in DC told of his being homeless and currently having wait listed 8 years for housing. Community activist Louise Thundercloud shared her personal fights with DC Council members characterizing the situation as “cultural genocide” and efforts by the moneyed establishment to destroy communities of color specifically Black and Latino.

One participant likened the situation to the West Bank Israeli settlements with the Palestinians being pushed off their homelands. The issue of affordable housing is not likely to go away. According to the Urban Institute the federal government provides housing assistance through rent subsidies, tax credits for building affordable housing, and block grants for affordable housing initiatives. But only about one of every four eligible households gets such aid. And subsidized housing is found disproportionately in distressed neighborhoods characterized by crime, poorly performing schools, and a lack of jobs.

Low-income families are being forced out of their communities similar to the forced displacement of Native Americans in the 1830s. The history lesson remains the same. Misguided government policies are doing more harm than good and by inadequately addressing the problem only perpetuates the cycle and generations of inescapable poverty and disadvantage. Chocolate City as the filmmaker declares does indeed stand as a call to action.

The Intouchables becoming an international box office hit

June 9, 2012

Since most Americans generally frown on foreign films particularly those with subtitles they will probably have to wait for the American remake of The Intouchables–the rights of which have been brought by The Weinstein Co. and probably now in the pipeline. Those who wait do so at a loss. The original is already the most watched film in France and quickly becoming an international box office hit having won the Tokyo International Film Festival best film award and the César Awards for best actor (the French equivalent to the American Oscar). Omar Sy is the first actor of African descent to receive a César for Best Actor. The Intouchables is 2012’s highest grossing move in a language other than English. That says much to those who have traveled abroad and seen how American films dominate foreign cinema.

Since most Americans generally frown on foreign films particularly those with subtitles they will probably have to wait for the American remake of The Intouchables–the rights of which have been brought by The Weinstein Co. and probably now in the pipeline. Those who wait do so at a loss. The original is already the most watched film in France and quickly becoming an international box office hit having won the Tokyo International Film Festival best film award and the César Awards for best actor (the French equivalent to the American Oscar). Omar Sy is the first actor of African descent to receive a César for Best Actor. The Intouchables is 2012’s highest grossing move in a language other than English. That says much to those who have traveled abroad and seen how American films dominate foreign cinema.

The Intouchables is based on a true story about the developing bond between a quadriplegic paralyzed from the neck down and an ex-con Black man who reluctantly becomes his caretaker. The wealthy Philippe played by Francois Cluzet lives in a luxurious Parisian mansion. Driss just out of prison from a six month robbery sentence shows up among a line of applying experienced white caretakers. Driss is not there for the job but a for signature verifying that he applied, the signature evidencing he meets the requirements for state benefits. But Philippe is drawn to Driss’s magnetic unflappable rambunctious and unrefined personality luring him into taking the job. Driss fights it every step away finally submitting to the mansion’s comfort and riches. Philippe introduces him to fine art and classical music while Driss in return offers lessons in American music through the sounds of Kool and the Gang and Earth Wind and Fire.

The employment relationship survives a 30 day probationary period overcoming the stress test sealing a bond, but the tests don’t stop here. Driss sets out on a constant quest to seduce Philippe’s secretary while coping with Phillip spoiled brat daughter. Driss too has his own handicaps. His mother kicks out of the house and a not being there for a younger brother involved in drug activities takes its toll on family. Then Driss discovers Philippe has a purely epistolary relationship with a German woman named Elenore and attempts to bring the pen-pal lovers together. The employer and employee become buddies each instinctively knowing how to serve one another.

Driss’ comedic quick witted response to white French bourgeois culture provides much of the stories comedic fodder. And it is incredibly funny with great writing, great cinematography and a sublime soundtrack blending both European classical music and American R&B.

Without a doubt much of this film’s success is attributable to Omar Sy’s superb acting. A minor accomplished French television actor Omar Sy is skyrocketing across the international screen with his portrayal of Driss. Hollywood’s new sought after hot talent was born in France to a Mauritanian mother and Senegalese father. One of eight children he grew up in a housing project 20 miles west of central Paris. Out of the housing project Sy similarly shares much with his character Driss. As quoted in the The Los Angeles Times [h]e speaks knowingly of “two Frances”–the stratum of the country that is wealthy and has access to the arts and the largely immigrant working class that does not. “The thing about this movie,” he said proudly, “is that it brought them together. People from one France came to the theater not knowing anything about the other France and they left having learned a lot, having sat together and laughed at the same jokes.”

Variety critic Jay Weisberg wrote a searing review calling it racist describing Driss as a performing monkey and “jolly house slave of yore, entertaining the master while embodying all the usual stereotypes about class and race.” As a Black man daily experiencing the vestiges of slavery and global racism first hand I was nevertheless thoroughly entertained. To Weisberg I say lighten up and laugh quoting Victor Hugo Laughter is the sun that drives winter from the human face.