Mark Twain and the Music That Moved Him Most

August 30, 2025

When the voices of Fisk’s Jubilee Singers struck Twain’s heart, he put his pen to work so the world could hear them too.

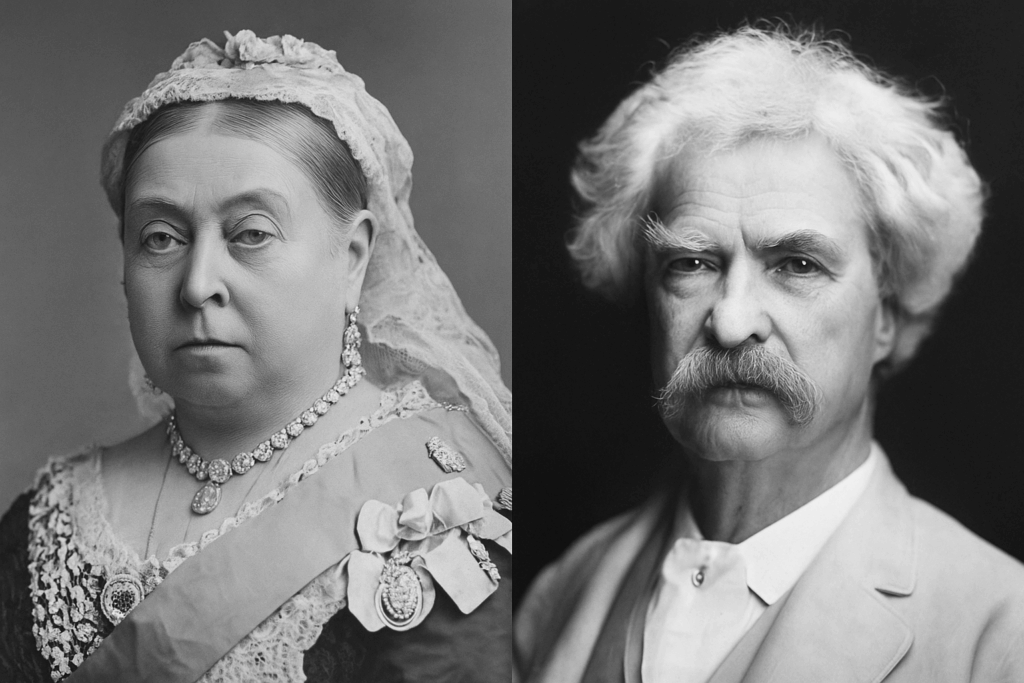

Osborne House, Isle of Wight UK 1873

The great doors of Osborne House swung open, and the young singers from Fisk University stepped into the royal drawing room. Their shoes clicked softly against the polished floor as they entered, eyes lowered, every movement stiff with composure. They were plainly dressed in dark gowns and modest coats, chosen for dignity rather than display. Behind their sober countenance lay a nervousness impossible to disguise.

Some had been born in slavery; others carried the fragile confidence of first-generation freedom. None could have imagined, when they left Nashville to raise money for a struggling school, that their voices would carry them here — before Queen Victoria herself. The silence of the chamber, the stern formality of the court, and the monarch’s piercing gaze pressed upon them with almost unbearable weight.

For a moment they stood still, honored yet overwhelmed. As soprano Maggie Porter later remembered, the Queen “listened with manifest pleasure,” but the singers themselves were uncertain of protocol:

“I wondered why the Queen did not speak these words to us,” Porter admitted, “for we were within hearing and heard her words of commendation and her command, but what could I know of English court etiquette.

Their apprehension, however, lasted only until George L. White, their leader, gave a small nod. At once the music began — a low, trembling entry that blossomed into the plaintive strains of Steal Away to Jesus. With the first notes, their fear fell away. The familiar harmonies steadied them, carrying them past doubt into the realm of song, where their duty lay.

The voices swelled, layering sorrow and hope into a sound that seemed to rise from history itself. For the singers, the weight of the moment dissolved into the power of their calling. For the Queen, it was a revelation. Victoria later recorded in her diary that they were “real negroes, eleven in number, six women and five men … they sing extremely well together.” She was visibly moved, and though her words were filtered through an attendant, her admiration was clear.

How Did They Get Here?

The image is astonishing: formerly enslaved youth from the American South, standing in the court of the most powerful monarch of the age. Yet the path from Nashville to Osborne House was neither smooth nor inevitable. It required not only the courage of the singers themselves, but also the advocacy of unexpected allies.

One of the most important — and perhaps the most enthusiastic — was Mark Twain. By 1873, Twain was America’s most famous author, his Innocents Abroad and Roughing It bestsellers on both sides of the Atlantic. He was also, improbably, a 19th-century groupie. When he heard the Jubilee Singers perform in Hartford, Connecticut, he was so overcome that he declared he “would walk seven miles to hear them again.” And unlike most admirers, Twain did more than applaud. He wrote letters, offered testimonials, and used his considerable fame to open doors that helped bring the Singers across the ocean and into Queen Victoria’s presence.

A Choir for a Cause

Fisk University, founded in 1866 in Nashville, was barely surviving by 1871. The buildings were ramshackle, funds nonexistent, and the mission of educating freedmen seemed at risk of collapse. George L. White, the school’s white treasurer and music instructor, had an audacious idea: take a group of Fisk’s best singers on tour to raise money.

The singers themselves were skeptical. The repertoire of African American spirituals was not considered respectable in the concert hall. White audiences expected comic “darky” songs or minstrel skits. But White and his students resolved to present the spirituals with dignity, as serious music and sacred testimony.

The experiment worked. Audiences in the North were spellbound. The troupe became known as the Fisk Jubilee Singers, named in reference to the biblical “year of Jubilee.” Yet as the tours lengthened, the young singers grew weary. Many were still teenagers. They faced racism on the road, endured long separations from home, and lived on scant meals. The group’s survival depended not only on their voices but on patrons who believed in them.

Twain Hears the Singers

One such patron was none other than Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

In 1873, Twain heard the Jubilee Singers perform in Hartford, Connecticut, where he had recently settled with his family. He was transfixed. The music stirred something deep within him — memories of the enslaved people he had known as a boy in Missouri, of the songs he had heard drifting from cabins along the Mississippi.

“I do not know when anything has so moved me as did the plaintive melodies of the Jubilee Singers,” Twain later wrote. He declared he would “walk seven miles to hear them again.”

For a man famous for his cynicism and satire, such words were startlingly earnest. Twain, it turned out, had become something of a 19th-century groupie.

A Literary Superstar Turned Publicist

Twain’s admiration went beyond private sentiment. He put his celebrity to work on the Singers’ behalf, acting almost like a modern influencer hyping his favorite band.

When the Jubilee Singers prepared to tour England, Twain wrote a glowing testimonial for them. Addressed to the editor Tom Hood and the London publisher George Routledge, his letter read in part:

“I heard them sing once, & I would walk seven miles to hear them sing again. … They reproduce the true melody of the plantations, & are the only persons I ever heard accomplish this on the public platform. The so-called ‘negro minstrels’ simply misrepresent the thing; I do not think they ever saw a plantation or ever heard a slave sing.”

For Twain, the distinction was critical. White minstrel shows had long mocked Black culture with grotesque caricatures. But the Jubilee Singers were the genuine article. “One must have been a slave himself,” he wrote, “in order to feel what that life was & so convey the pathos of it in the music.”

It was a bold statement from a Southern-born man whose father had owned enslaved people. Twain lent his authority as both a Southerner and a national celebrity to validate the Singers’ authenticity. His letter was published, circulated, and used to promote the Singers in Britain. It worked: audiences flocked, and doors opened.

Twain the Advocate

Why did Twain become such a vocal supporter? Part of the answer lies in his evolving views on race.

Though he grew up steeped in slavery, Twain became increasingly critical of racism as he matured. He later befriended Frederick Douglass, denounced lynching, and even paid tuition for Black students at Yale Law School and Harvard Medical School. His defense of the Jubilee Singers fit into this larger arc.

But there was also something personal. Twain’s literary genius thrived on exposing hypocrisy and celebrating authenticity. In the Jubilee Singers, he saw authenticity made audible. Their music wasn’t a show; it was lived experience transformed into art. For Twain, that demanded not just applause but action.

From Twain’s Pen to Victoria’s Ears

The impact of Twain’s fan-like advocacy was not trivial. His endorsement bolstered the Singers’ credibility as they crossed the Atlantic. In Britain, where Twain was already a celebrated author, his words helped convince skeptical patrons that the troupe deserved a hearing.

Once in London, the Singers attracted aristocrats, clergy, and philanthropists. Their cause aligned with Victorian ideals of moral uplift and Christian duty. It was through these networks that they secured an invitation to Osborne House.

Thus, when the Singers stood before Queen Victoria in 1873, they carried not only the weight of their own voices but also the momentum created by supporters like Twain. The Queen was so moved that she commissioned a formal group portrait of the singers, painted by her court artist Edmund Havel. Today, that portrait hangs in the Appleton Room of Jubilee Hall at Fisk University — a permanent reminder of how far their music carried them.

Twain as Groupie, Twain as Critic

The image of Mark Twain as a wide-eyed fanboy may seem at odds with his reputation as America’s great satirist. Yet it reveals something profound. Twain could be caustic about politics, religion, and human folly, but when he encountered truth and beauty, he responded with disarming sincerity.

In the Jubilee Singers, he found an art form immune to parody. He could lampoon politicians and preachers, but not the raw, soaring strains of Go Down, Moses sung by young men and women who had known slavery’s lash. For once, Twain dropped his mask of irony and simply applauded.

Conclusion: Twain’s Greatest Ovation

Mark Twain’s relationship with the Fisk Jubilee Singers was more than an episode of admiration. It was a moment when America’s most famous writer used his fame to amplify voices that the world might otherwise have ignored.

As a “19th-century groupie,” Twain wrote letters, offered testimony, and urged others to hear what he had heard. His words helped usher the Jubilee Singers from Nashville’s dirt floors to Europe’s gilded halls, from obscurity to a royal audience.

The singers saved Fisk University, raised the stature of African American spirituals, and left a legacy enshrined in song. Twain, in turn, left a legacy of fandom not for himself but for others.

Perhaps his greatest applause was not for his own jokes or books, but for a choir of emancipated youth whose music still echoes — in Jubilee Hall, in Nashville, and far beyond.