The Colored Section of Bookstores

September 20, 2011

by Yolanda M. Johnson-Bryant the founder and CEO of Bryant Consulting. Her consulting firm provides a variety of services to new and established writers, including ghost writing, manuscript editing, character development, and marketing. See YolandaMJohnson.com

and LiteraryWonders.com

African-Americans have come a long way in the literary industry. More and more black authors are emerging onto the markets, be in via traditional publishing or self-publishing. This is good news to our authors and readers, but we have to admit—we have a long way to go.

As authors, we have made our mark in bookstores. Let me correct that—non African-American bookstores. Now, when a patron walks into a bookstore such as Borders, Barnes and Noble or even Wal-mart, a reader can find our section with ease; the “colored section” if you will.

No, this is not about race—not necessarily. This is more so about activism. Should our books have their own section in bookstores? Yes and no. A consumer should be able to walk into a bookstore and browse bookshelves by genre like they can any other book. By doing so, would close yet another notch in the belt of segregation.

However, the reality is that a lot of African-American authors would lose out if this was to happen; right now at least. Currently, when a reader learns of a new book by their favorite author, or a new author, it is so easy for them to head straight to the “colored section” to find the book they are looking for, and even then, there is no guarantee the book will be available.

Another frustrating factor of the “colored section” is the lack of variety of our books and the lack of quantity. Many bookstores may confine AA (African-American) books to one kiosk, or at best, a two-sided book shelf or corral. I often wonder how African-Americans would feel if this section was larger. Would we complain about the segregation of our books then? Perhaps so; but I get the feeling that there would be less complaints about the section, and more complaints about something else.

Could it be that African-Americans cringe at the thought of actually having to socialize amongst the proper folk and subject themselves to something outside of their comfort zone? This could be it, or perhaps another factor could be that we don’t want to take the time that it would take to saunter somewhere other than the “colored section” to find the book we are searching for. I’d say that all of the above might be true.

Earlier, I mentioned that this was not a matter of race but activism. Bookstores don’t get a free pass when it comes to the part they play in the “colored section” because they are guilty, guilty, guilty! Contemplate this: Just like we made our presence known in the literary industry, we can also make our presence known in bookstores and make our voices heard. Everywhere you look, there is a campaign for this or a campaign for that. Why not start a campaign to either make the “colored section” larger and with more variety or mixing our titles amongst the “house books” if you will.

Talk to your local bookstore managers and associates, write letters, start a Facebook page—something other than Like Me if You Like My Farmville Page. Let’s also hold publishers accountable for joining forces with authors and readers so we can do something about that little violation problem in bookstores. African-Americans will boycott a local restaurant because they didn’t have catfish on the menu, but won’t boycott a bookstore so that our books will have a better presence in their establishment.

By doing this, we challenge our readers to come in from the cotton fields and mingle in the country club, and at the same time, expanding our horizons. As African-Americans, we can no longer sit about and complain about things and do nothing about them. With the takeover of e-books and the closing of bookstores, our books will be diluted in the process. Take action or kindly put up your Baptist finger and excuse yourself.

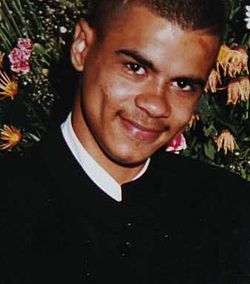

Mark Duggan

August 19, 2011

He was known as Starry Mark amongst his circle, but outside Tottenham London few had heard of Mark Duggan until August 4th when he died from a police inflicted gun shot wound. One witness reported the police shot Duggan at close range after they had pinned him to the ground. The investigation surrounding the shooting is being conducted by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPPC). Facts surrounding Duggan’s death remain murky. The 29 year old father of four was of mixed ancestry (British and Afro-Caribbean).

He was known as Starry Mark amongst his circle, but outside Tottenham London few had heard of Mark Duggan until August 4th when he died from a police inflicted gun shot wound. One witness reported the police shot Duggan at close range after they had pinned him to the ground. The investigation surrounding the shooting is being conducted by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPPC). Facts surrounding Duggan’s death remain murky. The 29 year old father of four was of mixed ancestry (British and Afro-Caribbean).

On August 6th Duggan’s relatives and local residents marched on the Totteham Police Station to demand information surrounding the circumstances of Duggan’s death. Some members of the crowd attacked two nearby police cars, setting them on fire. The incident sparked rioting across the city. Police officials later apologized for failing to provide information to the victim’s family in a timely manner and for providing the media with misleading information.

But for the police official’s failure to respond to family and public concerns the protest march and ensuing riot might not have occurred. In the aftermath the government’s swift crackdown and zero tolerance response under the guise of justice has been anything but with two people jailed for four years each for inciting riots on Facebook – riots that never took place – and one person sent to prison for six months for stealing $5 worth of water.

The British authorities are being criticized for its heavy handed reaction giving little attention to the causes behind the riots. Riots just don’t happen, but grow out a simmering discontent. Youth unemployment is the highest in 20 years. The British Office for National Statistics show the “inactive” population which comprises young people who are neither working nor unemployed stands at nearly 3 million, the highest level since the data was first collected in 1992. The analysis says two-thirds of these 16- to 24-year-olds are staying on in education, perhaps to stave off unemployment.

Compounding the problem in December British lawmakers pushed through a controversial hike in university tuition fees. Tens of thousands of angry students took to the streets of London and across the nation in protest arguing this effectively prices many out of a college education.

One wonders if similar signs of austerity and high youth unemployment in the States are likely with violent clashes signaling anti-establishment protests. In the 60s we saw African American communities destroyed by riots; many never recovered.

Austerity and riots take a heavy toll on the communities that can least afford them. Starry Mark wasn’t the cause of this riot but a human toll of global conditions.

On Boycotting The Help

August 10, 2011

There are grumblings of a boycott of the motion picture to be released this week. A number of African American writers and readers are in awe and miffed by the success of Kathryn Stockett’s The Help; miffed because a white author tells an essentially African American story from a black perspective using a black voice. They are in awe because the book achieved an author’s dream of success with a best seller and an accompanying movie deal, but there is more, a back-story for which the author is being rewarded with a law suit.

There are grumblings of a boycott of the motion picture to be released this week. A number of African American writers and readers are in awe and miffed by the success of Kathryn Stockett’s The Help; miffed because a white author tells an essentially African American story from a black perspective using a black voice. They are in awe because the book achieved an author’s dream of success with a best seller and an accompanying movie deal, but there is more, a back-story for which the author is being rewarded with a law suit.

The plaintiff Ablene Cooper, a 60 year-old woman who as recent as February worked for the Stocketts as a maid, Ms. Cooper argues that one of the book’s principal characters, Aibileen Clark is an unpermitted appropriation of her name and image, which she finds emotionally distressing. Cooper alleges Stockett promised not to use her name and likeness. How much Cooper contributed to the overall story remains unclear. There is legal precedence for Cooper’s claims.

Set in Jackson Mississippi the narrator Skeeter a white female journalism graduate relies on the maids’ housekeeping skills and knowledge to land a job as the newspaper’s housekeeping columnist, a subject of which she knows nothing. Talk about art imitating life, there are far too many similarities between the principal character, Aibileen Clark and Ablene Cooper right down to the gold tooth and the death of a child.

Whites taking and profiting from the stories and music of black folks misrepresenting their source and authorship has been a long standing practice. We recently discovered how Alan Lomax appropriated research of Black scholar John W Work, Lomax’s conduit to pioneering blues artists like Muddy Waters and Son House. Joel Chandler Harris profited from his Uncle Remus stories collected from Southern Blacks. Not to mention how young Elvis Presley sneaked into black churches and honky-tonks immersing himself into the sounds and rhythms he would later grow to imitate. There are hundreds if not thousands of stories of how African-American artistic expression has been misappropriated for the benefits of whites.

Given the negative evaluations of black culture and community coming from the larger white-dominated society this seems to be a part of our legacy where there is white privilege and limited opportunities for disadvantaged minorities to tell their own stories.

My only criticism is Stockett’s initial use of dialect which the author seems to abandon as her story progresses. Having spent some time in Jackson Mississippi I never noticed such dialect. Overall, I believe it is an important story that should be told. And the motion picture does provide opportunities for African American actors. I’m reminded of Hattie McDaniel’s declaration “I’ve rather play a maid than be one.” We take the bitter with the sweet. I wish the author well with lucrative rights and royalties and Ms. Cooper an even bigger settlement.

As for our cultural contributions I’m hopeful for the day when African-American writers and filmmakers in greater numbers will dazzle audiences with our remarkable stories.

I read The Help but won’t be in any theatre lines–not intentionally boycotting just waiting for the Netflix delivery.