Mark Twain and the Music That Moved Him Most

August 30, 2025

When the voices of Fisk’s Jubilee Singers struck Twain’s heart, he put his pen to work so the world could hear them too.

Osborne House, Isle of Wight UK 1873

The great doors of Osborne House swung open, and the young singers from Fisk University stepped into the royal drawing room. Their shoes clicked softly against the polished floor as they entered, eyes lowered, every movement stiff with composure. They were plainly dressed in dark gowns and modest coats, chosen for dignity rather than display. Behind their sober countenance lay a nervousness impossible to disguise.

Some had been born in slavery; others carried the fragile confidence of first-generation freedom. None could have imagined, when they left Nashville to raise money for a struggling school, that their voices would carry them here — before Queen Victoria herself. The silence of the chamber, the stern formality of the court, and the monarch’s piercing gaze pressed upon them with almost unbearable weight.

For a moment they stood still, honored yet overwhelmed. As soprano Maggie Porter later remembered, the Queen “listened with manifest pleasure,” but the singers themselves were uncertain of protocol:

“I wondered why the Queen did not speak these words to us,” Porter admitted, “for we were within hearing and heard her words of commendation and her command, but what could I know of English court etiquette.

Their apprehension, however, lasted only until George L. White, their leader, gave a small nod. At once the music began — a low, trembling entry that blossomed into the plaintive strains of Steal Away to Jesus. With the first notes, their fear fell away. The familiar harmonies steadied them, carrying them past doubt into the realm of song, where their duty lay.

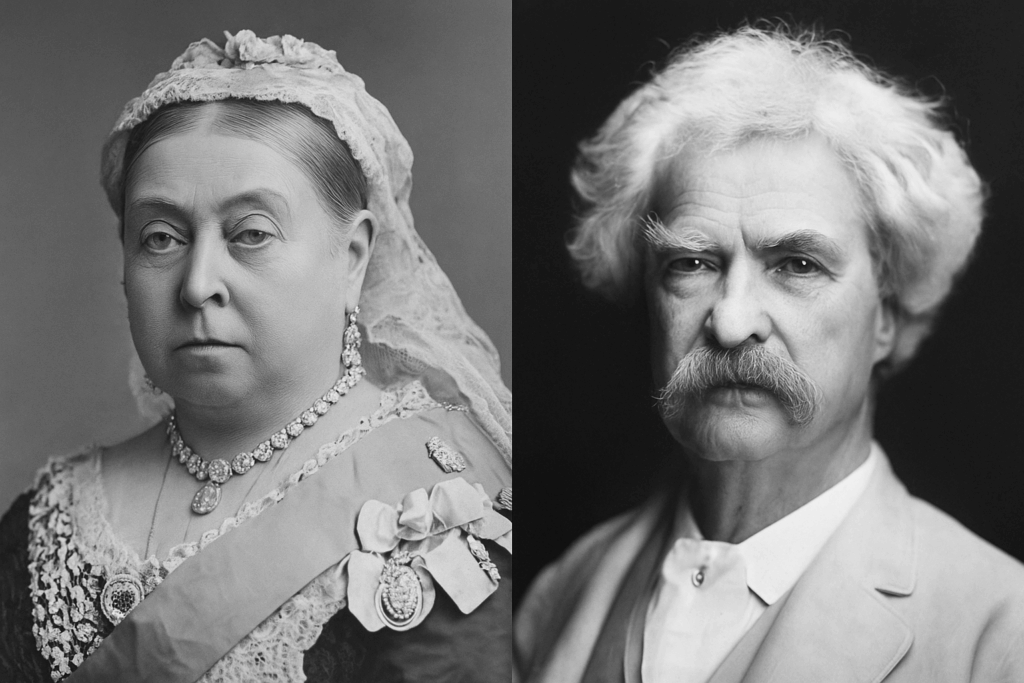

The voices swelled, layering sorrow and hope into a sound that seemed to rise from history itself. For the singers, the weight of the moment dissolved into the power of their calling. For the Queen, it was a revelation. Victoria later recorded in her diary that they were “real negroes, eleven in number, six women and five men … they sing extremely well together.” She was visibly moved, and though her words were filtered through an attendant, her admiration was clear.

How Did They Get Here?

The image is astonishing: formerly enslaved youth from the American South, standing in the court of the most powerful monarch of the age. Yet the path from Nashville to Osborne House was neither smooth nor inevitable. It required not only the courage of the singers themselves, but also the advocacy of unexpected allies.

One of the most important — and perhaps the most enthusiastic — was Mark Twain. By 1873, Twain was America’s most famous author, his Innocents Abroad and Roughing It bestsellers on both sides of the Atlantic. He was also, improbably, a 19th-century groupie. When he heard the Jubilee Singers perform in Hartford, Connecticut, he was so overcome that he declared he “would walk seven miles to hear them again.” And unlike most admirers, Twain did more than applaud. He wrote letters, offered testimonials, and used his considerable fame to open doors that helped bring the Singers across the ocean and into Queen Victoria’s presence.

A Choir for a Cause

Fisk University, founded in 1866 in Nashville, was barely surviving by 1871. The buildings were ramshackle, funds nonexistent, and the mission of educating freedmen seemed at risk of collapse. George L. White, the school’s white treasurer and music instructor, had an audacious idea: take a group of Fisk’s best singers on tour to raise money.

The singers themselves were skeptical. The repertoire of African American spirituals was not considered respectable in the concert hall. White audiences expected comic “darky” songs or minstrel skits. But White and his students resolved to present the spirituals with dignity, as serious music and sacred testimony.

The experiment worked. Audiences in the North were spellbound. The troupe became known as the Fisk Jubilee Singers, named in reference to the biblical “year of Jubilee.” Yet as the tours lengthened, the young singers grew weary. Many were still teenagers. They faced racism on the road, endured long separations from home, and lived on scant meals. The group’s survival depended not only on their voices but on patrons who believed in them.

Twain Hears the Singers

One such patron was none other than Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

In 1873, Twain heard the Jubilee Singers perform in Hartford, Connecticut, where he had recently settled with his family. He was transfixed. The music stirred something deep within him — memories of the enslaved people he had known as a boy in Missouri, of the songs he had heard drifting from cabins along the Mississippi.

“I do not know when anything has so moved me as did the plaintive melodies of the Jubilee Singers,” Twain later wrote. He declared he would “walk seven miles to hear them again.”

For a man famous for his cynicism and satire, such words were startlingly earnest. Twain, it turned out, had become something of a 19th-century groupie.

A Literary Superstar Turned Publicist

Twain’s admiration went beyond private sentiment. He put his celebrity to work on the Singers’ behalf, acting almost like a modern influencer hyping his favorite band.

When the Jubilee Singers prepared to tour England, Twain wrote a glowing testimonial for them. Addressed to the editor Tom Hood and the London publisher George Routledge, his letter read in part:

“I heard them sing once, & I would walk seven miles to hear them sing again. … They reproduce the true melody of the plantations, & are the only persons I ever heard accomplish this on the public platform. The so-called ‘negro minstrels’ simply misrepresent the thing; I do not think they ever saw a plantation or ever heard a slave sing.”

For Twain, the distinction was critical. White minstrel shows had long mocked Black culture with grotesque caricatures. But the Jubilee Singers were the genuine article. “One must have been a slave himself,” he wrote, “in order to feel what that life was & so convey the pathos of it in the music.”

It was a bold statement from a Southern-born man whose father had owned enslaved people. Twain lent his authority as both a Southerner and a national celebrity to validate the Singers’ authenticity. His letter was published, circulated, and used to promote the Singers in Britain. It worked: audiences flocked, and doors opened.

Twain the Advocate

Why did Twain become such a vocal supporter? Part of the answer lies in his evolving views on race.

Though he grew up steeped in slavery, Twain became increasingly critical of racism as he matured. He later befriended Frederick Douglass, denounced lynching, and even paid tuition for Black students at Yale Law School and Harvard Medical School. His defense of the Jubilee Singers fit into this larger arc.

But there was also something personal. Twain’s literary genius thrived on exposing hypocrisy and celebrating authenticity. In the Jubilee Singers, he saw authenticity made audible. Their music wasn’t a show; it was lived experience transformed into art. For Twain, that demanded not just applause but action.

From Twain’s Pen to Victoria’s Ears

The impact of Twain’s fan-like advocacy was not trivial. His endorsement bolstered the Singers’ credibility as they crossed the Atlantic. In Britain, where Twain was already a celebrated author, his words helped convince skeptical patrons that the troupe deserved a hearing.

Once in London, the Singers attracted aristocrats, clergy, and philanthropists. Their cause aligned with Victorian ideals of moral uplift and Christian duty. It was through these networks that they secured an invitation to Osborne House.

Thus, when the Singers stood before Queen Victoria in 1873, they carried not only the weight of their own voices but also the momentum created by supporters like Twain. The Queen was so moved that she commissioned a formal group portrait of the singers, painted by her court artist Edmund Havel. Today, that portrait hangs in the Appleton Room of Jubilee Hall at Fisk University — a permanent reminder of how far their music carried them.

Twain as Groupie, Twain as Critic

The image of Mark Twain as a wide-eyed fanboy may seem at odds with his reputation as America’s great satirist. Yet it reveals something profound. Twain could be caustic about politics, religion, and human folly, but when he encountered truth and beauty, he responded with disarming sincerity.

In the Jubilee Singers, he found an art form immune to parody. He could lampoon politicians and preachers, but not the raw, soaring strains of Go Down, Moses sung by young men and women who had known slavery’s lash. For once, Twain dropped his mask of irony and simply applauded.

Conclusion: Twain’s Greatest Ovation

Mark Twain’s relationship with the Fisk Jubilee Singers was more than an episode of admiration. It was a moment when America’s most famous writer used his fame to amplify voices that the world might otherwise have ignored.

As a “19th-century groupie,” Twain wrote letters, offered testimony, and urged others to hear what he had heard. His words helped usher the Jubilee Singers from Nashville’s dirt floors to Europe’s gilded halls, from obscurity to a royal audience.

The singers saved Fisk University, raised the stature of African American spirituals, and left a legacy enshrined in song. Twain, in turn, left a legacy of fandom not for himself but for others.

Perhaps his greatest applause was not for his own jokes or books, but for a choir of emancipated youth whose music still echoes — in Jubilee Hall, in Nashville, and far beyond.

Trump’s National Guard Presence in DC Is Bad for Business and Tourism

August 28, 2025

For residents, business owners, and visitors alike, the impact is immediate and damaging. A city that thrives on tourism and conventions cannot afford to project an image of intimidation and instability. When visitors are met not with open boulevards and welcoming guides but with checkpoints, armed patrols, and a climate of fear, the message is clear: this is not a place to relax, explore, or invest. According to recent news report Tour Guides are feeling it.

Washington, D.C. has always balanced two identities: the seat of American democracy and a vibrant world-class city. Millions visit each year for the museums, monuments, history, and culture that make the capital a global destination. But that balance is being undermined by the growing presence of heavily armed, politically aligned State National Guard forces deployed under Donald Trump’s direction.

Business Takes a Hit

D.C. hosts thousands of conferences and corporate gatherings every year, feeding hotels, restaurants, and local shops. These events depend on the perception of safety and openness. If the city begins to look and feel like a militarized zone, planners will take their events elsewhere—robbing the city of vital revenue and opportunities for growth.

Tourism Suffers Too

Families from across the country and international travelers come to Washington for a once-in-a-lifetime experience of democracy in action. What they expect is freedom of movement, cultural richness, and welcoming hospitality. What they increasingly encounter are scenes more fitting to a police state. For foreign visitors especially, this tarnishes America’s image as a nation of liberty and undermines Washington’s role as a showcase capital.

The Wrong Signal to the World

D.C. has weathered crises before—terror threats, mass protests, even insurrection. But those were moments, not the new normal. If Trump’s “police presence” is allowed to become permanent, it risks reshaping the city’s brand entirely. Instead of a hub of history and opportunity, it becomes a stage for political theater and intimidation. That’s not just bad optics. It’s bad economics.

Washington deserves better. The capital should be a place where democracy feels alive and accessible, not barricaded and patrolled. Protecting business and tourism means protecting the spirit of openness that makes the city thrive.

Israel’s Dangerous Path: Starvation, Silencing, and the Cost of Netanyahu’s Politics

August 26, 2025

Reports of Israel’s apparent policy of starving Palestinians and targeting journalists are both shocking and morally indefensible. These actions not only violate the principles of international law but also erode the foundations of human dignity. Starvation is not a weapon of war—it is an assault on humanity itself. The killing of journalists is not an accident of conflict—it is a deliberate attempt to silence truth and shield brutality from global accountability.

What makes this situation even more tragic is that it will bear consequences for generations. The legacy of deliberately inflicting hunger and death on civilians, while extinguishing voices of truth, ensures that any goodwill Israel once commanded will be replaced by anger, resentment, and bitterness that will endure for decades to come.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stands at the center of this crisis. His leadership has become defined not by safeguarding Israel’s future but by clinging to power. His policies reflect little concern for the Israeli hostages still in captivity. Instead of prioritizing their release, his government appears focused on prolonging war and conflict—an effort not to secure peace, but to extend his own political life.

This is not just bad for Palestinians. It is bad for Israel. It deepens Israel’s isolation, fuels extremism, and jeopardizes any hope of long-term security. The moral credibility of a nation cannot survive if it is built on collective punishment and censorship of truth.

History will remember these choices. And the verdict will not be kind.Silence in the face of injustice is complicity. Citizens everywhere must demand better—from Israel, from their own governments, and from international institutions. Write your representatives, support humanitarian organizations providing food and medical aid, and amplify the voices of journalists and truth-tellers who risk their lives to document reality. Pressure must be applied until the blockade of starvation is lifted, the protection of journalists is guaranteed, and genuine negotiations for peace are pursued.

The path forward cannot be built on hunger and repression. It must be built on justice, accountability, and humanity.

From the Margins to the Spotlight: Restoring the Legacies of Gilded Age Black Men of Distinction

August 11, 2025

The Real History Behind The Gilded Age’s Black Characters: African American Journalists and Physicians Who Defied Racism

Throughout American history, the stories of African American achievement have been diminished, denied, or outright ignored by the mainstream historical record. When African Americans of distinction did make it into press, their coverage was often couched in racist and condescending language, designed to belittle rather than celebrate their accomplishments.

The main stream press distorted many African American achievements. The press rarely honored their accomplishments. Through TV representation their stories are being rescued and revived. There is little published or known about the affluent Black life at the end of the 19th Century. HBO’s The Gilded Age has been instrumental in exploring the nuanced realities of the lives of affluent African Americans in the late 19th century.

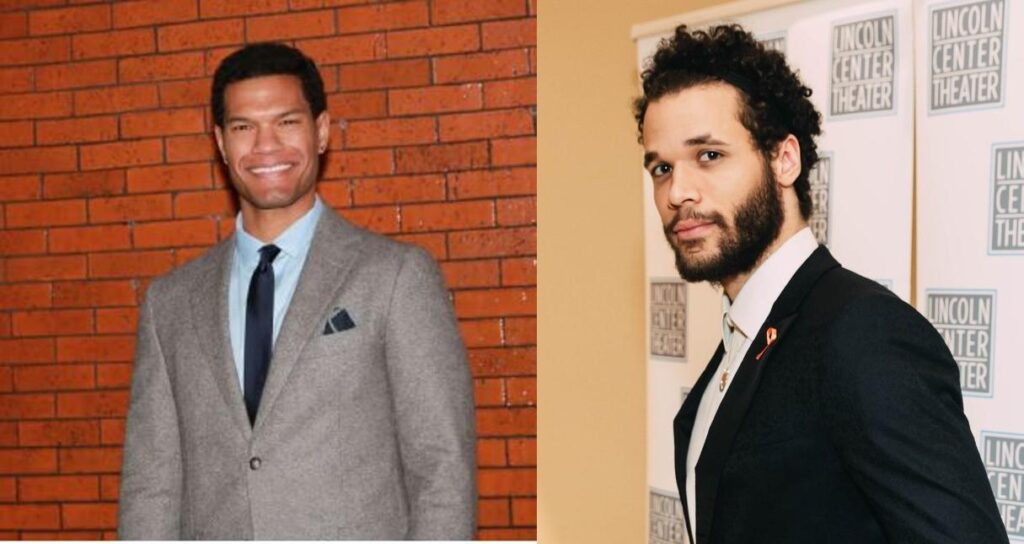

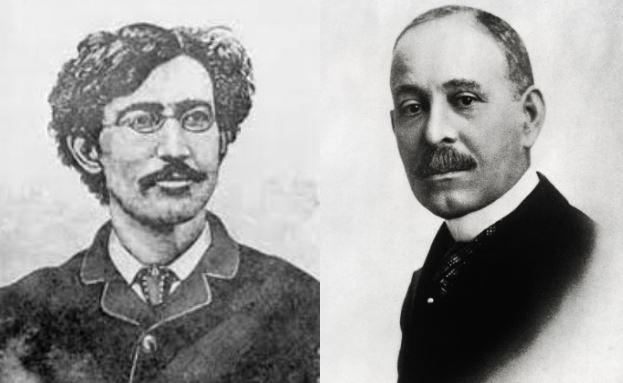

Two characters T. Thomas Fortune played by Sullivan Jones and Dr. William Kirkland played by Jordan Donica —offer a rare counterpoint to this tradition of erasure. Fortune is a real historical figure, one of the most respected African American journalists of his time. Kirkland is fictional, but his character draws upon the lives of several pioneering Black physicians, whose biographies remain largely unknown to the wider public. While there were a number African American physicians practicing in the U.S. from 1860-1890 many were froced find training in Canada and Europe.

T. Thomas Fortune (1856–1928), born into slavery in Florida, became the “Dean of Negro Journalists” and a leading voice against lynching, disenfranchisement, and segregation. Through his newspaper, the New York Age, Fortune championed civil rights, economic empowerment, and the dignity of African Americans during an era when white supremacy sought to crush both. In The Gilded Age, his depiction rings true, capturing both his intellectual vigor and his unshakable principles.

Dr. William Kirkland, though a fictional character, is rooted in historical precedent. His portrayal borrows elements from Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who performed one of the first successful open-heart surgeries and founded the nation’s first non-segregated hospital, and Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta, the first African American faculty member at a U.S. medical school—Howard University’s College of Medicine in 1868—and the first African American to be appointed as a surgeon with the rank of Major in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Augusta went on to head Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., and became a key figure in training future generations of Black physicians. In the latter part of the 19th century, numerous African American physicians practiced in the United States, but many had been forced to obtain their medical training in Canada or Europe due to racial barriers at home.

This was also the era in which eugenics—a pseudoscientific, racially biased theory that sought to justify white supremacy—was gaining intellectual traction among America’s political, academic, and medical elite. Eugenicists argued that African Americans were biologically inferior, using flawed data and biased studies to rationalize segregation and limit access to professional advancement. In medicine, these beliefs had devastating effects:

- Hospital Privileges Denied: Black physicians were systematically excluded from admitting privileges at white hospitals, forcing them to work in underfunded Black-only institutions with fewer resources and lower pay.

- Professional Isolation: Organizations such as the American Medical Association barred Black doctors from membership, isolating them from the latest research and professional networks.

- Medical School Discrimination: Eugenics advocates lobbied to limit the number of Black students admitted to medical schools, claiming they were unfit for the profession.

- Public Distrust: White supremacist propaganda fueled mistrust of Black doctors among white patients, effectively closing off a large segment of potential clientele.

Despite these barriers, Black physicians persevered—founding their own hospitals, medical societies, and training programs, often at great personal and financial sacrifice. Their resilience laid the groundwork for later generations of African American medical professionals and civil rights activists.

In the late 19th century, when the mainstream press covered men like Fortune or Williams at all, it was often through a lens of exoticism, condescension, or suspicion. The accomplishments of Black physicians were particularly underreported, buried in medical journals or Black-owned newspapers with limited reach. Period dramas like The Gilded Age and The Knick begin to fill this gap, offering audiences glimpses into the lives of these men. But selective storytelling is not enough—these narratives should be told with full historical fidelity to the Black experience.

Bringing these biographies back into the American consciousness is more than an act of historical recovery—it’s a reclamation of truth. These men were not outliers or footnotes; they were leaders in the ongoing struggle for equality, role models for their communities, and innovators in their professions. Whether through fictionalized television dramas, documentary films, or biographical features, their stories deserve to be told in a way that honors both their achievements and the barriers they overcame.

The erasure of Black excellence was intentional. Restoring it must be deliberate. By rescuing these lives from the edge of oblivion, we tell a fuller, more honest American story—and remind ourselves that the Gilded Age was not gilded for everyone, but it was also not without its Black luminaries, fighting to shape the future. #GildedAge, #AmericanHistory, #BlackHistory, #HistoricalFiction, #CivilRightsHistory

Getaway to Charlottesville

August 4, 2025

Two Plantations and a Vineyard

Charlottesville, nestled in the heart of Virginia, is where history, beauty, and leisure converge, wrapped in Southern charm, and where life’s pace lets you savor every moment. I traveled by train from Washington, DC, to visit Monticello, Montpelier, and a local vineyard. As a tour guide, I’m always looking out for local weekend getaways from which I can create future tours. Travelers from all over the world come to Washington, and many want to see Monticello. The trip’s purpose was a reconnaissance mission mapping how to make it happen. I did it with some ease and, in the process, discovered Charlottesville to be a hub of historical sites and leisurely activities. I spent two days visiting Monticello and Montpelier and lunched at Pippin Hill Farm and Vineyard.

I boarded an Amtrak Silver Star at Union Station. Seated backward, I watched the landscape from my window. The Capitol’s Statue of Freedom slowly faded into the eastern sky, as the Washington and Jefferson Memorials appeared and disappeared as the train crossed the Potomac into the Old Dominion, transforming a suburban landscape into the countryside. My daily world receded, being pulled away for some welcomed rest and recreation.

I was glad I didn’t drive, opting instead for the leisurely journey by train. It’s convenient, affordable, and a comfortable way to cover the 120 miles. As I get older, I find myself favoring public transportation over driving, appreciating the ease and relaxation it offers. For those considering this trip, especially if you’re staying in Washington for more than a couple of days, an overnight visit to Charlottesville provides numerous opportunities. You can immerse yourself and the kids in American history and plantation life, enjoy lunch at a winery, or soak up the local color at one of the many great dining establishments.

Pippin Hill Farm and Vineyards

Hydrangea Walkway approach to the restaurant.

Charlottesville’s wine country is part of the larger Monticello AVA (American Viticultural Area), named after Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate. This region is known for its rolling hills, fertile soil, and a climate that supports a wide variety of grape varieties, making it one of the premier wine destinations on the East Coast. Pippin Hill Farm and Vineyard is one of the standout wineries in the Charlottesville area, celebrated not only for its wines but also for its stunning views, farm-to-table dining, and elegant atmosphere. Located just a short drive from downtown Charlottesville, Pippin Hill is a popular spot for wine enthusiasts and those looking to experience the beauty and flavor of Virginia’s wine country.

Pippin Hill is known for its exceptional menu, which emphasizes locally sourced, seasonal ingredients. The cuisine is farm-to-table, reflecting the bounty of the surrounding region. The menu often includes fresh salads, artisanal cheeses, charcuterie boards, gourmet sandwiches, and entrees that highlight local meats and produce. The dishes are designed to complement the wines produced at the vineyard, offering a complete sensory experience that marries food and wine.

Pippin Hill produces a variety of wines, with a focus on grapes that thrive in Virginia’s climate, such as Viognier, Chardonnay, Cabernet Franc, and Merlot. They also produce sparkling wines, Petit Verdot, and Rosé. The Rosé at Pippin Hill is particularly well-regarded. It’s often described as crisp, refreshing, and balanced, with notes of red berries, citrus, and a hint of floral aroma. This Rosé is a perfect pairing for many of the dishes on their menu, especially during the warmer months, making it a favorite among visitors.

Monticello

Thomas Jefferson is best known for authoring the Declaration of Independence and serving as the third President of the United States, during which he orchestrated the Louisiana Purchase, significantly expanding U.S. territory. He is also celebrated for his contributions to the founding principles of American democracy and for founding the University of Virginia, reflecting his deep commitment to education and the intellectual growth of the nation.

Although I am critical of the enslavers, my observations from my visit to Monticello highlight its efforts to give voice to the enslaved experience. My lineage traces back to the enslaved at Mount Vernon, and I am an active member of the League of the Descendants of the Enslaved at Mount Vernon. Curious about the life of the enslaved, my primary purpose in visiting these presidential estates was to learn about their daily lives.

Monticello offers a variety of tours, from general highlights to specialized ones, including the “From Slavery to Freedom” tour that I participated in. This tour provided a deep dive into the Hemings family and the lives of other enslaved families. I was particularly moved by the wooden wall with the names of the enslaved carved into it. This installation serves as a poignant reminder of the individuals who contributed to the estate’s operations and maintenance, helping visitors and scholars alike recognize the integral role that these individuals played in the history of the plantation.

Monticello’s specialized tours aim to provide a fuller, more nuanced understanding of Thomas Jefferson’s contributions to the United States and the integral roles played by the people, both free and enslaved, who lived and worked at Monticello. Jefferson’s complex relationships with the enslaved individuals at Monticello offer a window into the contradictions that many founding fathers faced—espousing freedom and human rights while simultaneously participating in and benefiting from the institution of slavery. His legacy in this regard continues to prompt reevaluation and discussion about the moral foundations of America’s early leaders.

My takeaway is that Monticello sets a standard for memorializing the lives and contributions of the enslaved, a group that until recently was disregarded as insignificant to the American narrative. Monticello does much more to elevate their stories than other presidential historical institutions.

Montpelier

Montpelier, the historic plantation home of James Madison, the fourth President of the United States, is beautifully situated in the bucolic setting of Virginia’s Piedmont region, nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The estate spans over 2,650 acres of rolling landscapes and dense forests, offering a picturesque glimpse into the past. This tranquil setting features expansive views of the surrounding countryside, marked by lush greenery and well-preserved 18th-century architectural structures. Visitors can explore the meticulously restored mansion, stroll through the heritage old-growth forests, and wander among the gardens that have been maintained to reflect the era of Madison’s occupancy. The serene natural environment and the historical depth of the plantation provide a vivid window into the early American republic and the complex legacy of one of its Founding Fathers.

Madison’s home, Montpelier, in Virginia, became a center of political discussion and development. Like Jefferson’s Monticello, Montpelier is now a place where visitors can learn not only about Madison’s life and contributions but also about the lives of the enslaved individuals who lived and worked there.

Secretary of State and President: As Secretary of State under President Jefferson, Madison supervised the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States. Architect of the Constitution

Madison’s home, Montpelier, in Virginia, became a center of political discussion and development. Like Jefferson’s Monticello, Montpelier is now a place where visitors can learn not only about Madison’s life and contributions but also about the lives of the enslaved individuals who lived and worked there. James Madison, often referred to as the “Father of the Constitution,” was a complex figure whose character, personality, and vision had a profound impact on the formation of the United States. Madison was known for his intellectual rigor, meticulousness, and foresight. He was not particularly charismatic in the traditional sense; he was reserved, soft-spoken, and physically slight, but his intellectual prowess and ability to articulate complex ideas clearly and persuasively made him a formidable thinker and strategist.

Along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, Madison authored the Federalist Papers, a series of essays defending the proposed Constitution to the public. These papers remain some of the most important documents in American political theory, offering insight into the intentions of the framers and the theoretical foundation of the U.S. government. Recognizing the concerns of those wary of a too-powerful central government, Madison played a pivotal role in drafting the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution that guarantee individual liberties such as freedom of speech, assembly, and religion.

A major takeaway from a visit to James Madison’s Montpelier would be a deeper understanding of the complex legacy of the “Father of the Constitution.” Visitors can explore how Madison’s profound contributions to the founding of the United States and the crafting of the Constitution coexist with his status as a slave owner. Montpelier offers insights into Madison’s political philosophies, his personal life, and the lives of the enslaved individuals who lived and worked on the estate.

The property has been meticulously restored to reflect its historical significance and includes exhibits that tell a fuller story of American history by incorporating the perspectives of the enslaved community. The site also engages with themes of constitutional democracy, civil rights, and the ongoing impact of slavery in America, making it a profoundly educational experience that connects past and present.

Three oustanding meals, dinner at The Local, Pippin Hill Lunch, and Riverside Lunch

h guide erxploring local weekend getaways, my recent trip from Washington, D.C., by train to visit Monticello, Montpelier, and the Pippin Hill Farm and Vineyard was both a reconnaissance mission and a delightful journey through the area’s rich cultural landscape. Charlottesville is not only a hub of historical sites but also offers a myriad of leisurely activities, making it a popular destination for tourists worldwide who seek an accessible yet enriching experience of America’s past. The blend of historical exploration at presidential estates and relaxing vineyard visits provides a comprehensive experience of both the historical depth and the natural beauty of this unique region.